Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight

In iconography, fidelity to tradition is more important than the assertion of the artist’s will. As Bertrand Davezac writes in his essay The Icon and the Museum, “the idiosyncrasy of the hand,” is not as important as “subservience to tradition” (17). This means that the iconographer must make images that conform to tradition, as opposed to breaking from it. In that sense, the personality of the iconographer is not as significant as the icon itself.

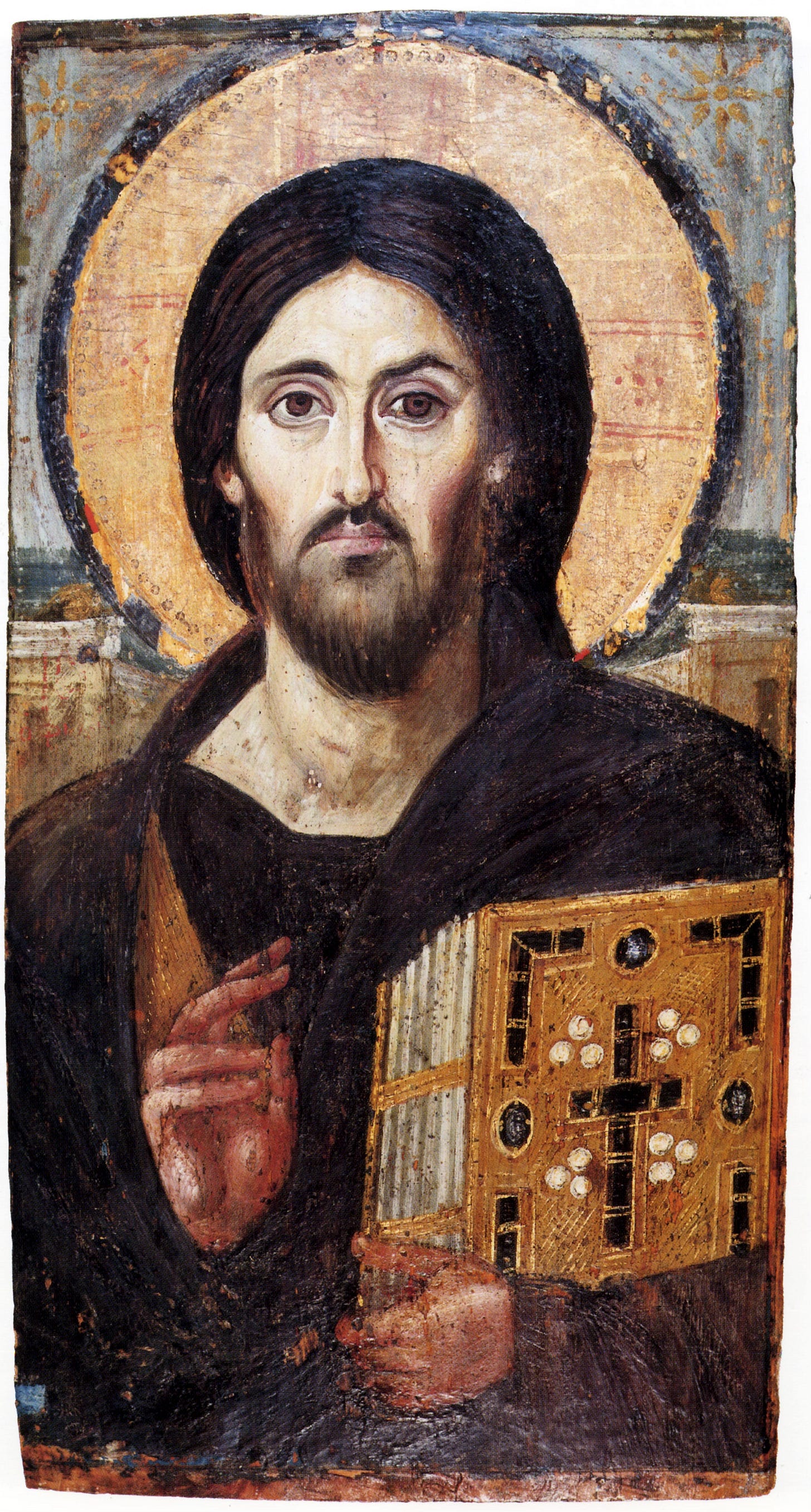

It goes without saying, but icons are inherently flat. For those of us who are accustomed to a more naturalistic image, an icon can be jarring. There is a sense in which the features are elongated, and the expressions feel almost blank. It’s necessary to understand that an icon is meant to convey a transfigured state; it’s meant to depict a heavenly reality. Therefore, an icon, like tradition, is not bound by time.

Christ Pantocrator (Sinai) is thought to be one of the oldest and most recognizable icons in the world. While this particular painting is encaustic on panel, it’s common to see this type of image on the ceiling of an Orthodox Church looking over the congregation. Pantocrator means “ruler of all,” so it makes sense why he would positioned in an area that reinforces this title.

This image captures the dual nature of Christ, as being both fully God and fully man. This is shown through the treatment of the eyes. While the expression can feel a bit unnerving, it’s meant to convey both justice and mercy. Therefore, we should approach this image with humility. Like most icons, He is depicted in a space that feels timeless. This is reinforced through the use of gold, which is used in icon painting to reference the uncreated light of God.

I want to compare this image alongside another one created by Albrecht Dürer entitled Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight. This is also another iconographic image by Dürer where he is assuming a pose typically reserved for Christ. Made in the year 1500, this painting shows him processing some of the ideas that would lead to the Reformation seventeen years later. Charles Taylor writes that, “Protestantism is…attempting to raise general standards, not satisfied with a world in which only a few integrally fulfill the gospel, but trying to make certain pious practices absolutely general” (82). In other words, to fully appreciate Dürer’s painting it should be viewed alongside a line of thinking that attempts to dignify everyone as being created in the Image of God.

Given the absence of a background, he was obviously creating a work that was meant to have a timeless quality. The lack of space causes you to focus in on Dürer himself. His face glows, given the muted tones surrounding him, and this suggests that the “uncreated light” is within him (us). Unlike Christ Pantocrator (Sinai), Dürer’s expression lacks severity, making him more approachable. His hand is raised toward his heart in a supposed sign of blessing, yet he’s careful to direct it back toward himself. He’s not so audacious to assume the role of God, but he’s clearly acknowledging conventional depictions of Christ that came before him.

What I find compelling about this image is the tension it creates. In A Secular Age, Charles Taylor writes,

The realism, tenderness, physicality, particularity of much of this painting, instead of being read as a turning away from transcendence, should be grasped in a devotional context, as a powerful affirmation of the Incarnation, an attempt to live it more fully by bringing it completely into our world (144).

If all of this is true, I don’t believe that Dürer was purposely trying to disenchant; his intention was not to turn our eyes away from Christ. Rather, it looks like he is attempting to process the implications of the Incarnation, and the ways that it can hallow “the ordinary contexts of life” (144). His painting seems to say that Christ is no longer in the tabernacle, but rather, he is in the heart.