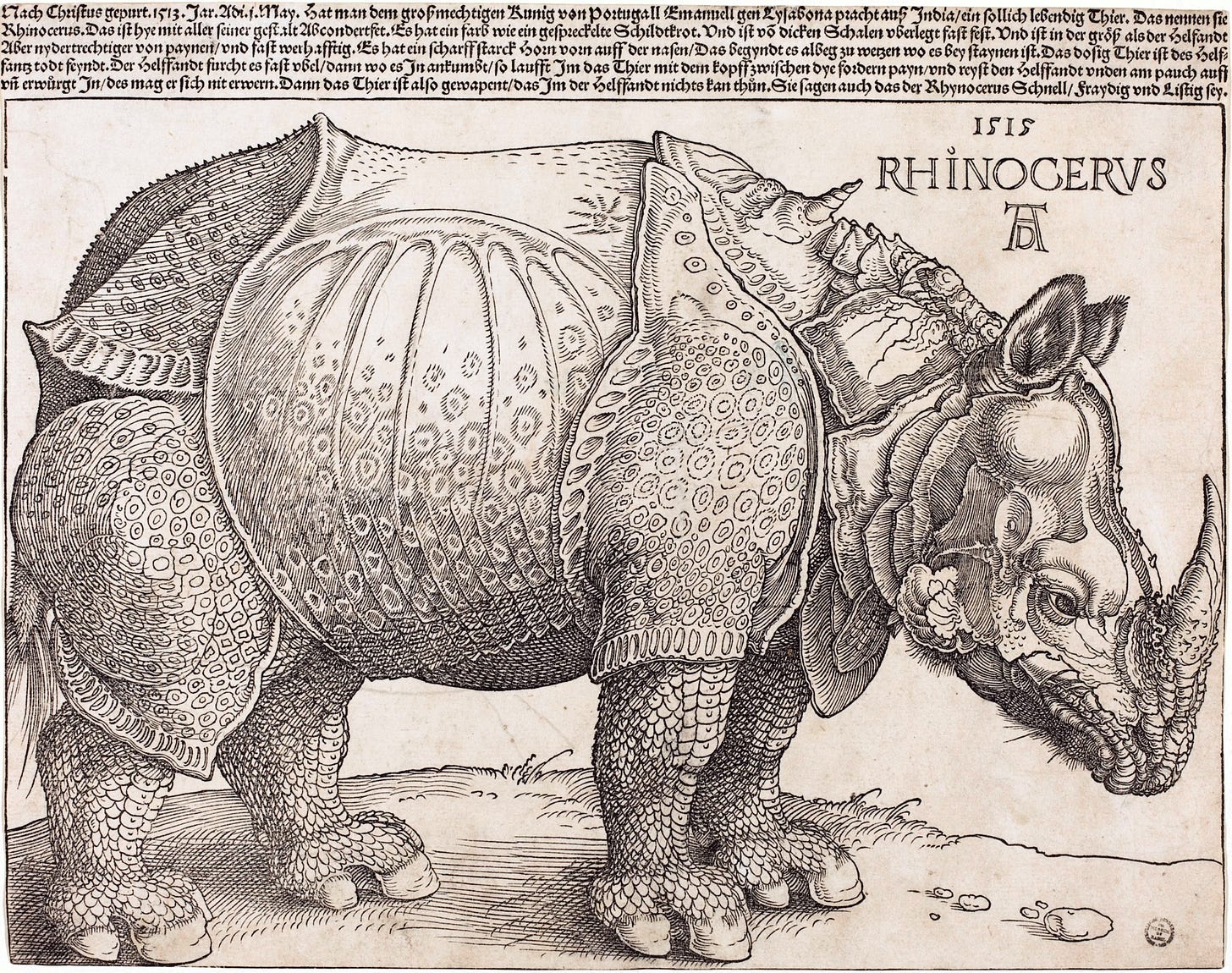

The Rhinoceros

In the year 15[1]3 on 1 May was brought to our King of Portugal to Lisbon such a living animal from India called a rhinoceros. Because it is such a marvel, I had to send it to you in this representation made after it. It has the color of a toad and is covered and well protected with thick scales, and in size it is as large as an elephant, but lower, and is the deadly enemy of the elephant. It has on the front of the nose a strong sharp horn: and when this animal comes near the elephant to fight, it always first whets its horn on the stones and runs at the elephant pushing its head between his forelegs. Then it rips the elephant open where the skin is thinnest and then gores him. Therefore, the elephant fears the rhinoceros; for he always gores him whenever he meets an elephant. For he is well armed, very lively and alert. The animal is called rhinoceros in Greek and Latin but in India, gomda.

This inscription is at the bottom of Albrecht Dürer’s drawing of a rhinoceros. When he translated his drawing into the medium of woodcut, he made some changes to the inscription that clearly informed his depiction of the animal. The woodcut describes the rhinoceros in the following manner:

On 1 May 1513 was brought from India to the great and powerful king Emanuel of Portugal to Lisbon such a live animal called a rhinoceros. It is represented here in its complete form. It has the color of a speckled tortoise and it is covered and well covered with thick plates. It is like an elephant in size, but lower on its hind legs and almost invulnerable. It has a strong sharp horn on the front of its nose which it always begins sharpening when it is near rocks. The obstinate animal is the elephant’s deadly enemy. The elephant is very frightened of it as, when it encounters it, it runs with its head down between its front legs and gores the stomach of the elephant and throttles it, and the elephant cannot fend it off. Because the animal is so well armed, there is nothing that the elephant cannot do to it. It is also said that the rhinoceros is fast, lively, and cunning.

In reading both of these accounts, I’m struck by his decision to leave out any association to a toad, even though the texture of both animals is very similar. (See here and here.) Obviously, there’s nothing threatening about a toad, while an animal that is “well covered in thick plates” would certainly seem to be built for combat. All the same, while the “thick scales” are omitted from the woodcut’s inscription, they are clearly incorporated into his image.

In her essay, Dürer’s Indexical Fantasy: The Rhinoceros and Printmaking, Susan Dackerman states, “The change in animal described to define color is indicative of a consequential transformation in the conception of the rhinoceros’s outer covering. Toads’ bodies are covered with soft skin, while speckled tortoises are housed in hard, textured shells” (168). If the rhino is “the deadly enemy of the elephant,” then it would make sense why Dürer changed the inscription from a toad to a tortoise – from soft skin to a hard shell. To coat the rhino in armor is to prepare the animal for battle. Additionally, while the Indian rhinoceros has a single horn, Dürer depicts an animal that has an additional horn protruding from its back, reinforcing the violent undertones built into his image. Yes, elephants and rhinos do occasionally come into conflict, but it’s a fairly rare occurrence. Dürer wouldn’t know this, however, given that he never saw a rhinoceros, let alone observed one in the wild. Regardless, these changes make for a highly compelling image. The accuracy of Dürer’s Rhinoceros is especially remarkable since all he had to go on was a sketch and written description. His print, then, is an amalgamation of the original inscription and his interpretation.

Dackerman continues:

The depiction of these “unnatural” features was not a mistranslation of the original drawing, as has been claimed, but a deliberate exaggeration of the characteristics intended to draw attention to, and thematize, the artist’s printmaking practice…Dürer’s woodcut rhinoceros is caught between the impulse toward the faithful depiction of nature and the drive to invent new forms that rival it (165).

Anyone can see when looking at Dürer’s oeuvre that he is an artist who is concerned with precision. This is evident when looking at his observational drawings. And yet, according to Dackerman, Dürer’s decision to alter the rhinoceros is intentional; his woodcut is primarily about his depiction of the animal. If the rhinoceros no longer has any connection to a toad; if the body of the rhinoceros is now meant to be seen as “armor,” then inevitably our perception of the rhinoceros will change. Since Dürer was not able to see the rhinoceros in person, there was no way for him to gauge whether his version captured the essence of the animal. The question to ask is whether his alteration gets us closer to the rhinoceros or pushes us away. The more I’ve reflected on Dürer’s Rhinoceros, the more I’ve thought about it through the lens of Craig Gay’s book Modern Technology and the Human Future. Gay writes:

Rather than existing in dialogue with the larger world outside of our heads…we moderns have instead become narrowly preoccupied with our own projects of making and with the “uses” that we find within these projects for the “stuff” that we find in the world. We have, therefore, become very largely blind and deaf to the marvelous “otherness” of the world (128).

Gay is working through Heidegger’s concept of “enframing,” which is “a way of ‘seeing’ the world and ourselves, and of envisioning human purposes in the world” (120). Enframing creates a one-sided relationship by objectifying the world, prohibiting us from “truly listening to given nature” (122). This might not seem like a big deal, except it causes us to lose “the possibility of encountering something outside of ourselves that might direct and discipline – and thus give order to – human making and willing” (129). If, as Dackerman states, The Rhinoceros is an attempt to create a form that rivals nature, then the ability to “dialogue with the larger world outside of our heads” is greatly reduced. If Dürer is more concerned with what he can get out of the rhinoceros, then we are left to grapple with the implications of that decision. As Gay states:

Our knowledge of ourselves is never direct. It is reflected back to us in the relations that we have with “others,” which includes our lived environment. If these relations are stunted and/or distorted, they will reflect back an image of ourselves that is also stunted and/or distorted (120)

Dürer’s decision to translate the rhinoceros into woodcut allowed him to disseminate this image to a larger audience. To read, “It is represented here in its complete form” is to assume that Dürer has encountered the animal, thereby providing assurance that his representation of the rhinoceros is correct. However, as mentioned, Dürer’s drawing has been translated from a sketch and written description, which is then turned into a woodcut. Regardless of how accurate his image is, it’s being filtered through multiple mediums. While there is an interpretive component to all art, I’m interested in the way this can gradually remove us from a true engagement with the world. If Dürer’s Rhinoceros was made in order to “invent new forms that rival nature,” as Susan Dackerman says, then it’s worth considering how his image might actually “reflect back an image of ourselves that is stunted and/or distorted.” In other words, if his image was not solely concerned with the faithful depiction of nature, then The Rhinoceros might actually distort our perception of nature, regardless of whether his image opens us up to the “marvelous otherness” of the world. This means that the incremental adjustments made to the inscription are not neutral decisions, but initiate a process that has the capacity to disconnect us from nature entirely. This can be seen in the book Changing Our Minds by philosopher S. Kay Toombs. Toombs writes the following:

Children at a museum exhibit that featured two giant live turtles from the Galápagos Islands preferred robotic turtles because the real ones didn’t “do” anything, and aliveness comes with inconvenience (15).

And:

Children are losing the ability to distinguish between living and nonliving things or to give proper value judgements as to which is preferable…a friend from Dubai – a totally urban, technology-saturated environment – told us that the first time her child saw a live dog, she exclaimed in wonder, “Wow, how many batteries does that thing take?” (15)

If Toombs anecdotal evidence is indicative of our present condition, then it’s worth tracking the way images develop our perception of the world. While it’s possible to project onto an image something that isn’t there, I also think it’s worth asking what sort of possibilities an image can generate. Playing with representations of nature will inevitably condition the way we perceive the world. Images shape our vision and condition our assumptions. Though Dürer’s modifications might’ve been intended to draw attention to his printmaking practice, his woodcut is in some sense distorted – Dürer’s embellishments to the rhinoceros are not simply stylistic decisions, but rather, they shape our perception of the animal. In part, I believe that this was Dürer’s intention; his woodcut actually helps us to see the rhinoceros. Truth be told, I believe this is part of Dackerman’s proposal. Given that he never saw a rhinoceros, it’s remarkable that his image ended up being a placeholder for one. In an age that is inundated with images, this is no small thing. And yet, as mentioned in my previous post, if we stop at a resemblance of a rhinoceros, failing to view it in relation to the animal it represents, we miss out on the opportunity to have a true encounter with the world.