The Sea Monster

In his book Albert and the Whale, Philip Hoare describes The Rhinoceros in the following manner:

In Dürer’s divine harmony, animals took on an emblematic role. He saw them the way a monk read the scriptures, or an astronomer peered at the sky. His rhino is interplanetary, pitted with lunar craters; erupting with coral reefs; jewel-laden as any tortoise, carved as any Venetian grotto chair. And as Dürer cut him into wood, Ganda became even more crenellated and encrusted, the way little oysters grow on bigger ones. In his days at sea, Ganda had acquired new markings, a kind of fungus, the way algae appears on the backs of whales and seals.

Dürer conflated all animals in one. He added a second spike to the chine of the rhino, not a horn at all but the helical tusk of a narwhal, as if this beast had a real unicorn within him and was only waiting to cast off that onerous, clunky hide. Whales, walruses, mammoths, rhinos: a strange fraternity, lingering after-images in our heads.

Hoare’s description of The Rhinoceros is poetic, casting it in a mythological light alongside dragons and sea monsters. In fact, it’s fair to say that Dürer’s depiction shows us an animal that is more comfortable at sea than on land. Surely, the fate of the rhino played into his image; as it sank to the bottom of the sea, it emerged as a shape in his imagination. His print puts us into contact with a prehistoric form, but more importantly it realigns the boundaries of our world. As I reflect on Dürer’s Rhinoceros, I wonder if it is closer to a sea monster than what I initially realized.

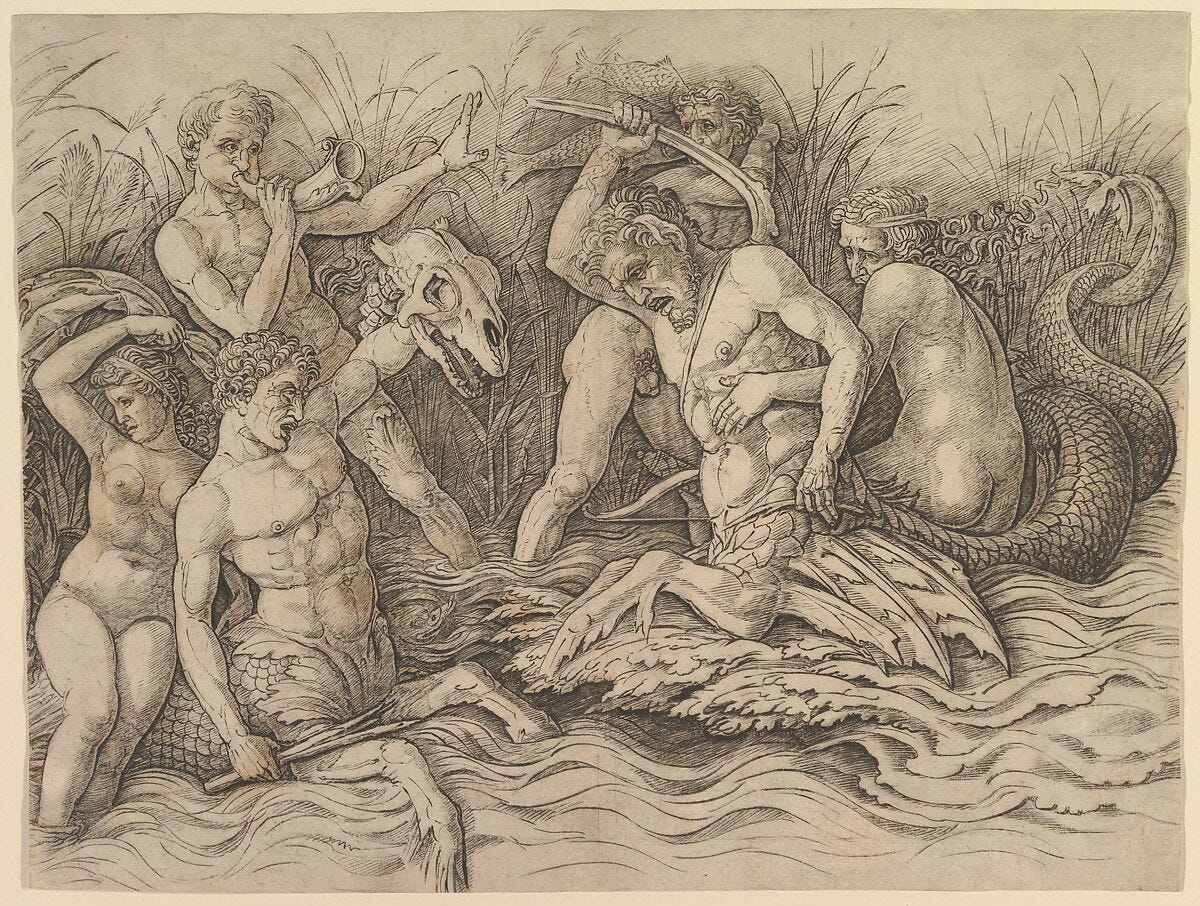

The Sea Monster is an engraving by Albrecht Dürer completed in the year 1498. He made this print a few years after journeying to Venice. This trip undoubtedly informed his composition, as it gave him the opportunity to interact with the work of Andrea Mantegna, an artist who was deeply influential to Dürer – he spent considerable time copying his work. This engagement inevitably gave shape to The Sea Monster, as the monster makes direct reference to Battle of the Sea Gods.

While the compositions are different, the sea monster could easily be a character in Mantegna’s engraving. (Interestingly enough, it almost looks like a rhinoceros skull is situated at the center of Mantegna’s composition.) Both artists were clearly influenced by Greek mythology, even though Dürer’s image is not based on any one particular story. As Christof Metzger states, “None of the many proposed interpretations is convincing since none of the abduction cases known from antiquity corresponds to the action illustrated here” (218). Rather, Dürer’s engraving seems to have a different objective, which lies in rendering the body of the naked woman, a body that is based on a classical ideal. He’s clearly drawing from a range of different sources in order to construct his image.

The Sea Monster was made near the tail end of the Age of Discovery, a time that allowed “previously isolated parts of the world to become connected.” Undoubtedly, seafarers would have brought back tales of sea monsters and other mythological beasts, providing Dürer with plenty of material for his image. Additionally, given his own propensity for travel, he would have certainly accumulated stories as he visited different regions. The Rhinoceros, like The Sea Monster, emerged out of this same space. According to Christof Metzger, The Rhinoceros was “conceived as a spectacular means of satisfying the craving of his contemporaries for information and sensation, especially regarding newly discovered worlds” (368).

The more I look at Dürer’s prints, the more I think that he was trying to process the way mythologies simultaneously mold and challenge our understanding of the world. Of course, his imagery is visually complex, but that’s not the reason I keep returning to it. Dürer is an artist who circles back to his previous work as he gives shape to new forms. The Sea Monster is not simply a work of imagination, but rather it plays a critical role in how he visualized The Rhinoceros. Both of these pieces share formal qualities that suggest these are creatures that have emerged out of the same space. Dürer was not making arbitrary decisions as he rendered his rhino, but rather he wanted to reinforce the mythologies that were foundational to western culture. As I reflect on the armor of the rhinoceros, I can’t help but think that he was meditating on the armature of the world.